On the last day before a holiday weekend, I thought I’d talk about something that’s important for us marketers but also fun. Or at least it should be. The topic of improving slideshow presentations has been covered wonderfully in the past, but there are some great new perspectives you should be checking out, to keep your Powerpoint decks in check.

(With so many co-workers starting the holiday early today, one of the stalwart few who will be with me in the office today joked that he’d bring Mimosas. From that last riff you’d think he’d followed through on the threat!)

Merlin Mann of 43 Folders gave a wonderful presentation to Google recently on better use of email. His 50 minute presentation (the video is below, and here’s a podcast of the talk) was as fun as it was practical. In response to inquiries, he shared his Powerpoint tips in a recent post. Although I should mention that he is the second person this week to let me know that Keynote has it over Powerpoint, if only because you can look at your speaking notes on your computer’s monitor while the audience sees the projected slide.

In his tips on better slideshows, Merlin mentions Guy Kawasaki’s 10-20-30 Rule: “A PowerPoint presentation should have ten slides, last no more than twenty minutes, and contain no font smaller than thirty points.” This reminded me of another slideshow presentation form (I say form, just as poetry has its classic sonnet and haiku forms). I’m thinking of the form called pecha kucha.

Pecha kucha was invented four years ago in Tokyo by Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham of Klein Dytham Architecture. They created it as a way to attract people to an event space they’d set up. They wanted a freeform presentation environment that wasn’t hackneyed. Sort of an un-poetry slam.

Here are the rules for a Pecha Kucha night: A number of presenters (usually 14) each does a slideshow of exactly 20 images, each lasting exactly 20 seconds. That puts the total runtime at 6 minutes, 40 seconds. The topics of the presentation vary widely, but the presenters are primarily artists and designers. These events have spread, to take place in major cities around the world. I’m tempted to attend the next one in Chicago, in late September.

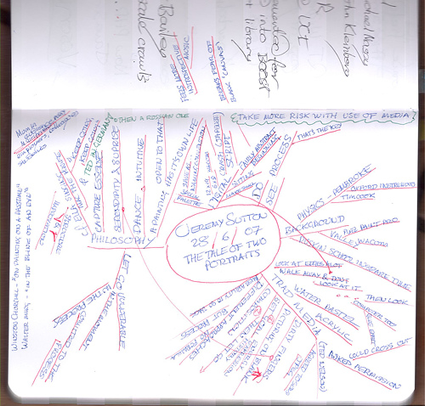

According to an uncited entry in Wikipedia, this 20 slides, 20 seconds each form has been adopted in some corners of the business world. It allows for a brief, disciplined presentation of ideas, with questions withheld until the end and no room for meandering on the part of the speaker. It’s all in the service of avoiding “death by Powerpoint.” Those who know me well are aware that I dislike using Powerpoint, and try whenever possible to present with a simple MindManager mind map. Or just write out my ideas into a Word document (there, Microsoft, at least you get some of my loyalty!)Â and speak without visuals. It’s all in the worship of one of my business heros: Edward Tufte.

For my friends reading this in the U.S., have a wonderful Labor Day Weekend, devoid of Powerpoint — unless you like that kind of thing!