Last week I suggested that the top-down style of Senator Clinton’s primary campaign may have hindered her effectiveness in competing against Obama’s more networked approach. I wrote that this may be a sign of a new type of leadership — possibly one that can use burgeoning digital networks to lead us out of the dark, scary, physically isolating forest of modern digital life.

This forest is exemplified by the findings in the book Bowling Alone, by Robert D. Putnam. It is also placed into stark contrast by Senator Clinton’s ideal, as outlined in her book, It Takes a Village. The subtext in the African phrase “It takes a village to raise a child” is that no one or two people can raise a well-balanced and fully engaged citizen. At the very least, the task requires an extended family. Ideally there is a whole community at work.

The fear that a network cannot replace a village is — I think — a major source of anxiety about our newly wired world.

Of Televisions and Suburbs

Some would say Putnam (in Bowling Alone) didn’t chart the trend toward physical sprawl and fragmentation far enough. If he had, he might have found its earlier origins. He seems to place the apogee of American social capital somewhere between the administrations of FDR and Jimmy Carter. Before and after that, according to Putnam’s statistics, are the steep sides of a bell curve.

But looked at farther back, this bell might possibly be a blip.

If you look at its root causes, community disintegration might have actually started (silently, unmeasured), much closer to the time of Abe Lincoln. Consider the first game-changing technologies our young country was handed: The steam locomotive and the telegraph.

At the time, they were of huge significance. And these technologies were just the first gateway drugs for our current wanderlust.

After we gained the ability to settle across this country, our urge to strike out was further abetted by the automobile, and then the passenger jet. Nuclear families — and the neighborhoods supporting them — both suffered, as we were granted license by technology. Each successive device seemed to give us further permission to gather in smaller groups, and watch over narrower concerns.

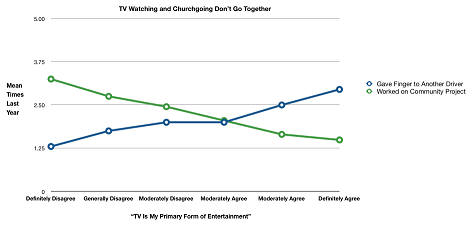

So don’t be quick to heap all of the blame on what is, after all, merely the newest shady character in the police line-up. Networks and portable digital communication are the least familiar technologies, and therefore the most scary. But many others before them have been implicated in our decline. For example, before the web there was the “vast wasteland” of television.

Networks: A Cause Or Effect?

It may even be that networks can be a big part of “the way out of the forest.” Something has been telling me that the situation is more complicated than a steady march toward alienatation. I’m not the first to post these arguments. In his 2007 paper, David Koepsell suggests the following:

The web could well be, and in many ways still is, a highly alienating technology, encouraging a one-to-one relationship with a machine that even TV does not encourage. That is to say, television can be watched in groups, and often is, leading to a form of community interaction that the web typically does not.

However, the emergence of social networking through the web has brought about new methods for otherwise alienated and occasionally isolated people to overcome that isolation, to build new modes of affiliation, and form new communities in both virtual and physical spaces.

Koepsell suggests that no technology is embraced unless it meets some fundamental human needs. But do the latest technologies go far enough to begin restoring some of our society’s waning social capital?

My money is on Yes. But it is hard to see how this will happen, because we have lived with this type of networked world for so little time. Although it’s possible society has a terminal illness that no amount of networked leadership can reverse, it’s equally possible in my mind that our diminished social capital is a symptom of growing pains.

Could it be that, as a society, we’re just at that awkward age?

A Study of Semantics

Rereading this entry, I see the metaphors come hot and heavy. That’s not surprising. And it’s important to understand how desperate we all are for something to grab onto (yes, another metaphor!).

I’m reminded of something Al Gore said, when he was being interviewed on a chartered jet during his 2000 Presidential run. He was talking about his love of learning, and the courses he had recently taken on a number of important topics. When he was asked what he would likely pursue next, given everything a potential president should know, he said semantics.

Gore went on to say that technology and society are changing so fast, our language is straining to keep up. Here’s an excerpt, from the July 31, 2000, New Yorker article:

“Often the word ‘metaphor’ is simply a shorthand description for a very common, run-of-the-mill intellectual tool that all of us use.

“I became interested in more complex metaphors and their explanatory power when I was writing Earth in the Balance. In particular, in my effort to try to understand the origins of our modern world view, and its curious reliance on specialization and ever-narrower slices of the world around us into categories that are then themselves dissected, in an ongoing process of separation, into parts and subparts — a process that sometimes obliterates the connection to the whole and the appreciation for context and the deeper meanings that can’t really be found in the atomized parts of the whole — and in exploring the roots of that way of looking at the world, I found a lot of metaphors in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that came directly from the scientific revolution into the world of politics and culture and sociology. And many of those metaphors are still with us.”

Such as?

“The clockwork universe. The idea that all the world is a machine of moving parts that will eventually be completely understood by means of looking carefully at all the different gears and cogs in the wheels and then …” He trailed off; he seemed to be searching for an exact phrase, and as he did this he turned his head in profile, squeezed his eyes shut, and made a pointing gesture with his hand. Then, when the words came, he turned his head back to me and smiled engagingly. “When I compared the absolute number of new scientific insights that came in the first flush of the scientific revolution to the incredible flood of scientific insights that now pour out of every single discipline, every single day, it’s astonishing. There’s no comparison. And yet the migration of those explanatory metaphors, from the narrow niches of science into the broader public dialogue about how we live our lives and how we understand the human experience and how we can better solve the social problems that become more pressing with each passing decade — that migration is, has been, reduced to the barest trickle.”

Gore seems to be saying here that we need fresh metaphors to properly share and debate developments in this new, digital landscape. We need to build a new linguistic toolkit — especially to deal with a world that is, on its surface, purely conceptual.

I agree.

If we can keep talking — and especially if we seek to understand — we’ll be on our way to a better world. I frankly don’t see an alternative. So as unworthy as I am to contribute, I’m glad that in a small way I can add to the dialog.

I’m certainly no expert in such matters. So I polled several who were as I prepared this set of posts. My favorite feedback came from youth and technology authority danah boyd, in a brief but much-appreciated email. To my concerns about our trajectory deeper into a “bowling alone world,” she provided some qualified reassurances (and a little research guidance).

What are your thoughts on this important matter? How are you taking action as an individual to create new and sustainable communities?